“Soil Like Toothpaste”: The Making of Brisbane Airport’s Ambitious New Runway

Captain Chesley Sullenberger (aka Sully) isn’t the only pilot to be landing his aircraft on a river. The new Brisbane Airport runway opened on 12 July 2020, situated on a reclaimed portion of the Brisbane River delta (a landform created by sediment carried by a river depositing at its mouth).

The successful completion of the project marks the realisation of a 50-year vision for Brisbane Airport and almost 8 years of construction, in what is one of the biggest engineering feats in Australian aviation project history.

“It’d be great if there were a few more planes landing on it,” laughs Brisbane Airport Corporation’s project director for the new runway, Paul Coughlan.

Site preparation alone took 5 years due to the sensitive nature of dredging in Moreton Bay and the extremely poor quality of soil at the site of the reclamation.

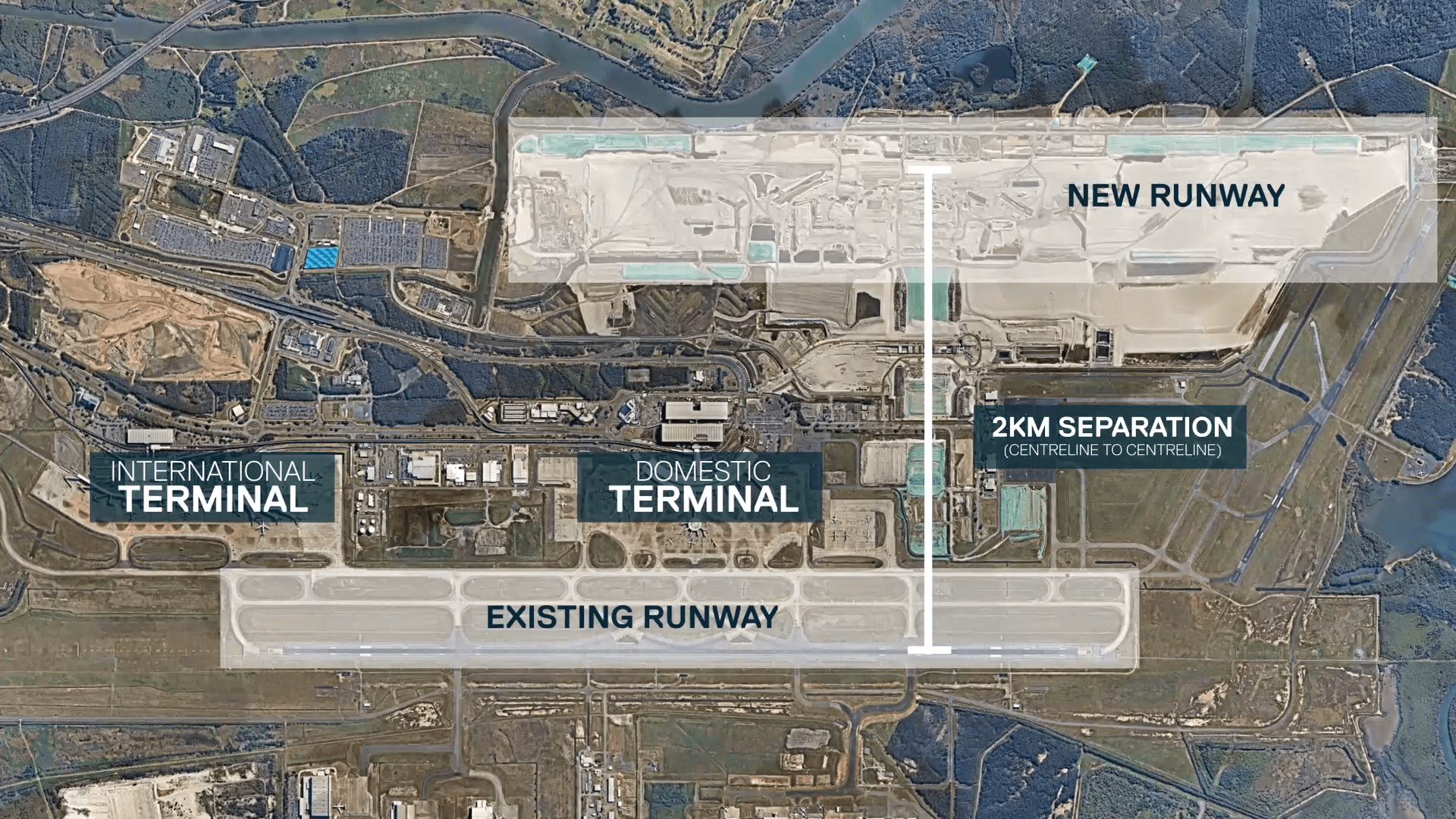

The project also included a new 3.3 km parallel runway, 12 kms of taxiways, high intensity approach lighting systems (HIAL), 300ha of landscaping, a four-lane underpass, and a 1.7 km revetment wall.

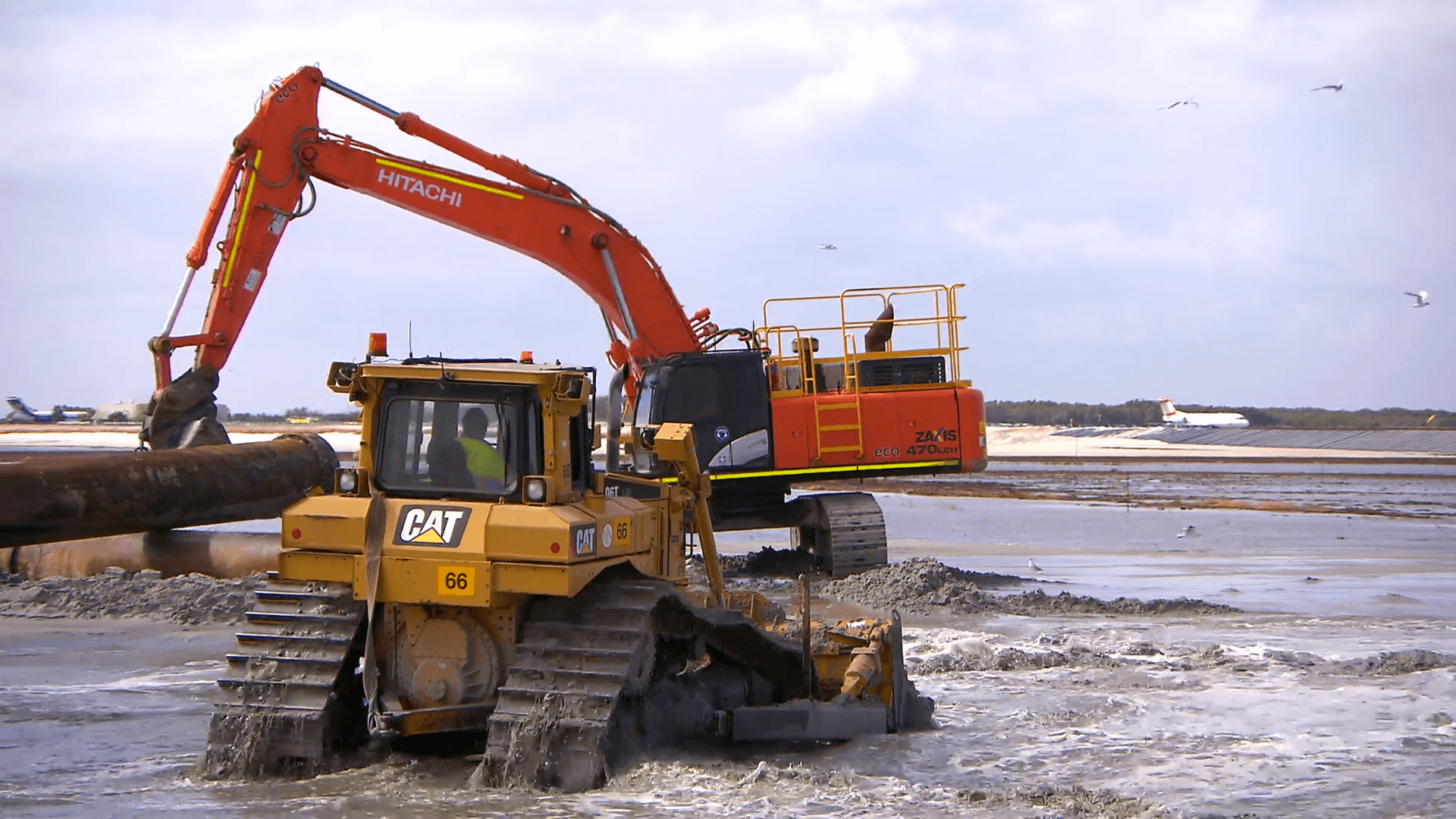

“Dredging and reclamation works in Brisbane’s backyard of Moreton Bay, was always going to be a monumental challenge,” says Coughlan, “It was extremely important to us that we didn’t leave any impact on the bay.”

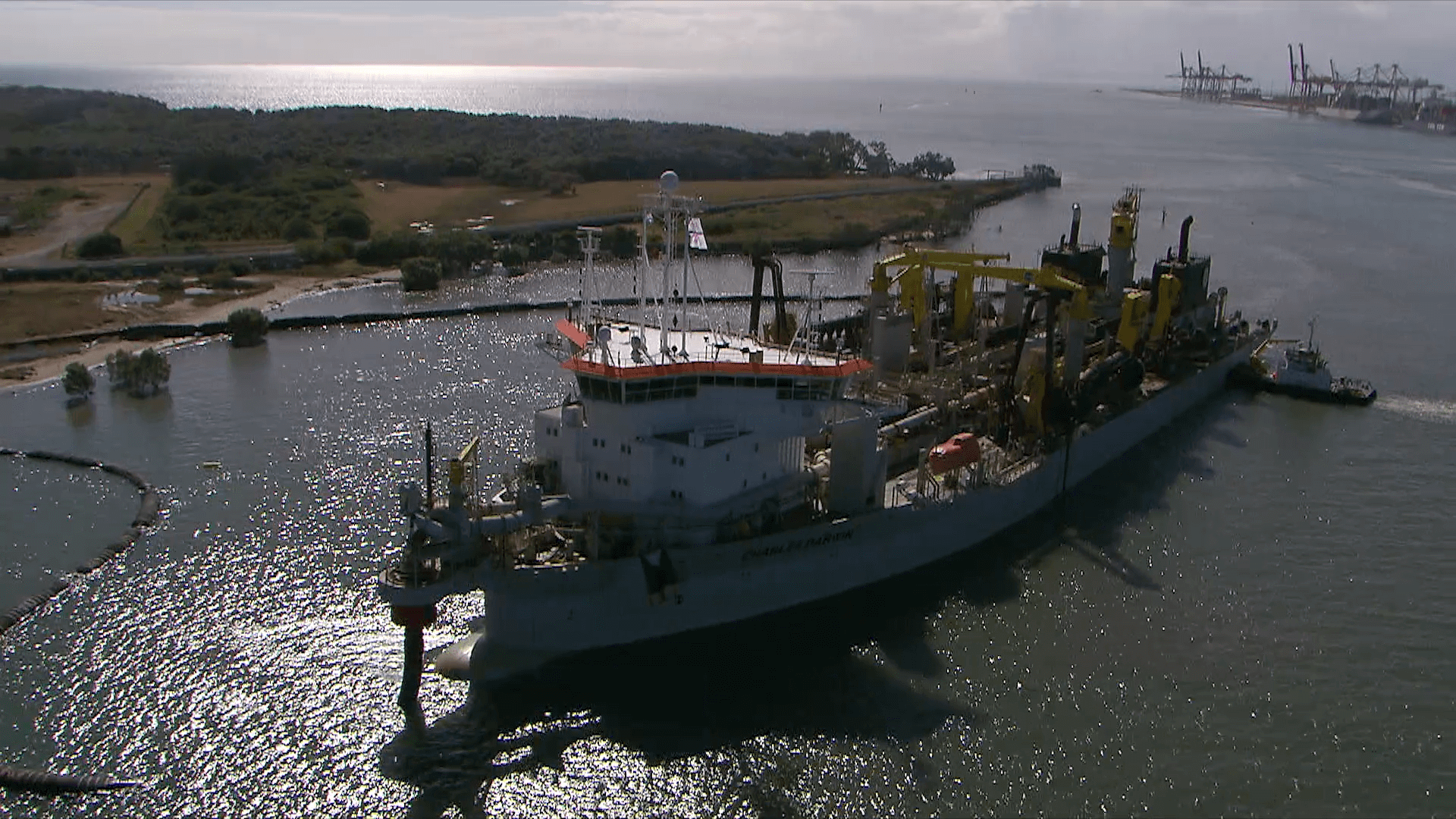

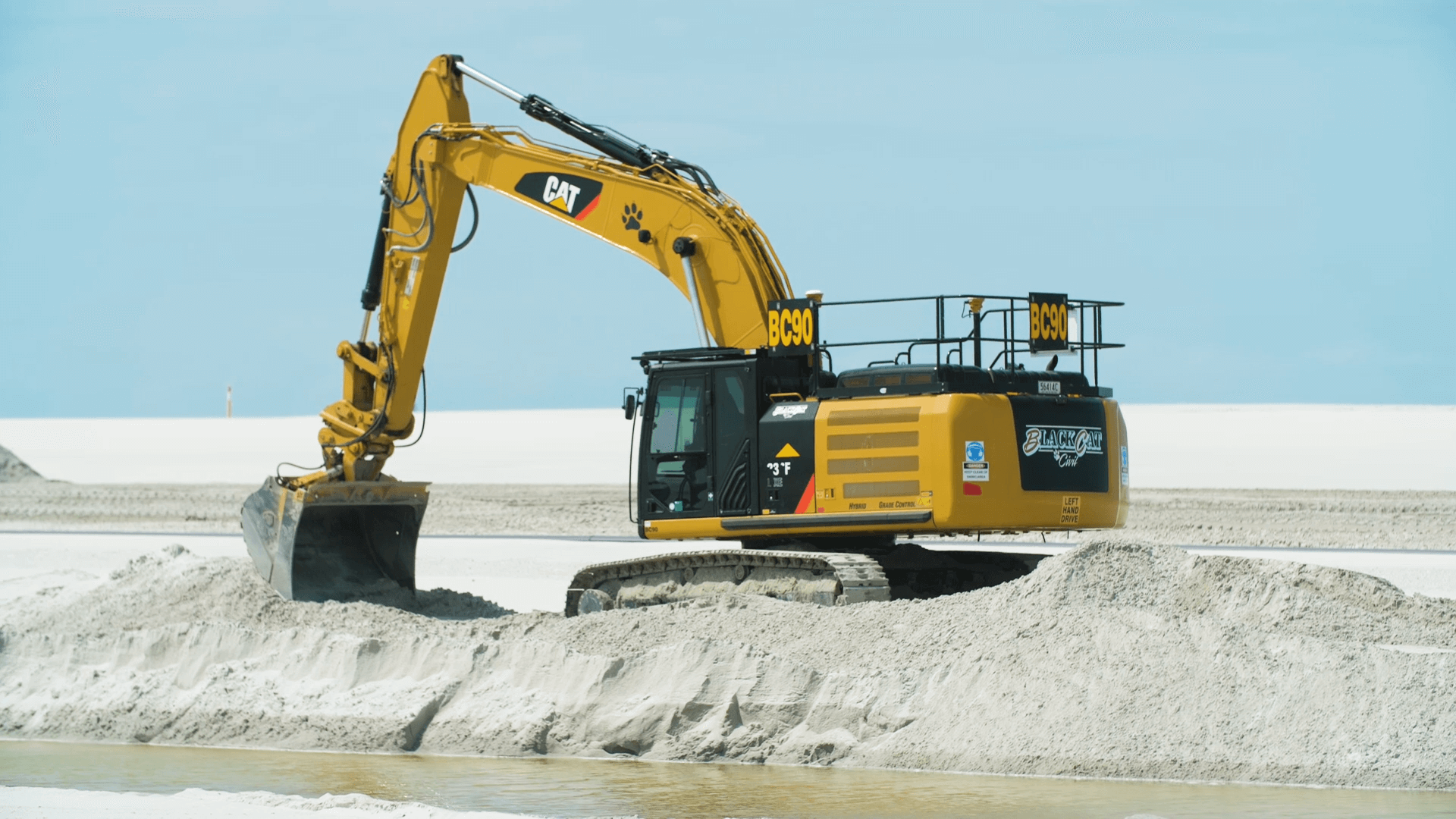

11 million cubic metres of very fine, D50 sand (250 microns) was dredged from Moreton Bay and used as fill to raise the 360 ha site above flood level and provide a stable foundation. One of the world’s largest dredging vessels, the 180-metre (approx.) Charles Darwin, was brought over from Europe by Belgian dredging contractor, Jan De Nul.

The Charles Darwin is a trailer suction hopper dredge (TSHD) consisting of powerful suction tubes equipped with a drag head which was used to draw sand from Moreton Bay into its hopper where it could store 30,500 m3 until the ship moored. Once moored, the Charles Darwin pumped a mixture of sand and water through a 4.5 km pipeline to the reclamation site.

What made this project truly ambitious, was the condition of the soil at the runway site, which has often been described as resembling the ‘consistency of toothpaste.’

“The soil quality was the worst anyone had ever seen at the airport - there were doubts as to whether the project was feasible,” says Coughlan.

The geotechnical investigations reported vegetation and topsoil were lying over:

- A crust of surface soils approximately 1.0 m deep; over

- Compressible materials (typically sandy clays and clayey sands) to between 7 m and 12 m in depth;

- Compressible silty clays to between 10 m and 32 m in depth; and

- Stiff clay and dense sands below the compressible materials.

The soil consisted of a California Bearing Ratio (CBR) between 1 and 1.5 - typical runway projects would be built on 10 or greater.

To achieve the required stability of the soil, modelling suggested that a 5-year period would be required after filling to allow sufficient ground settlement. But this timeline was going to render the whole project infeasible.

The core design team for the reclamation works comprised of AECOM, Golder & Associates and Brisbane Airport Corporation’s internal designers.

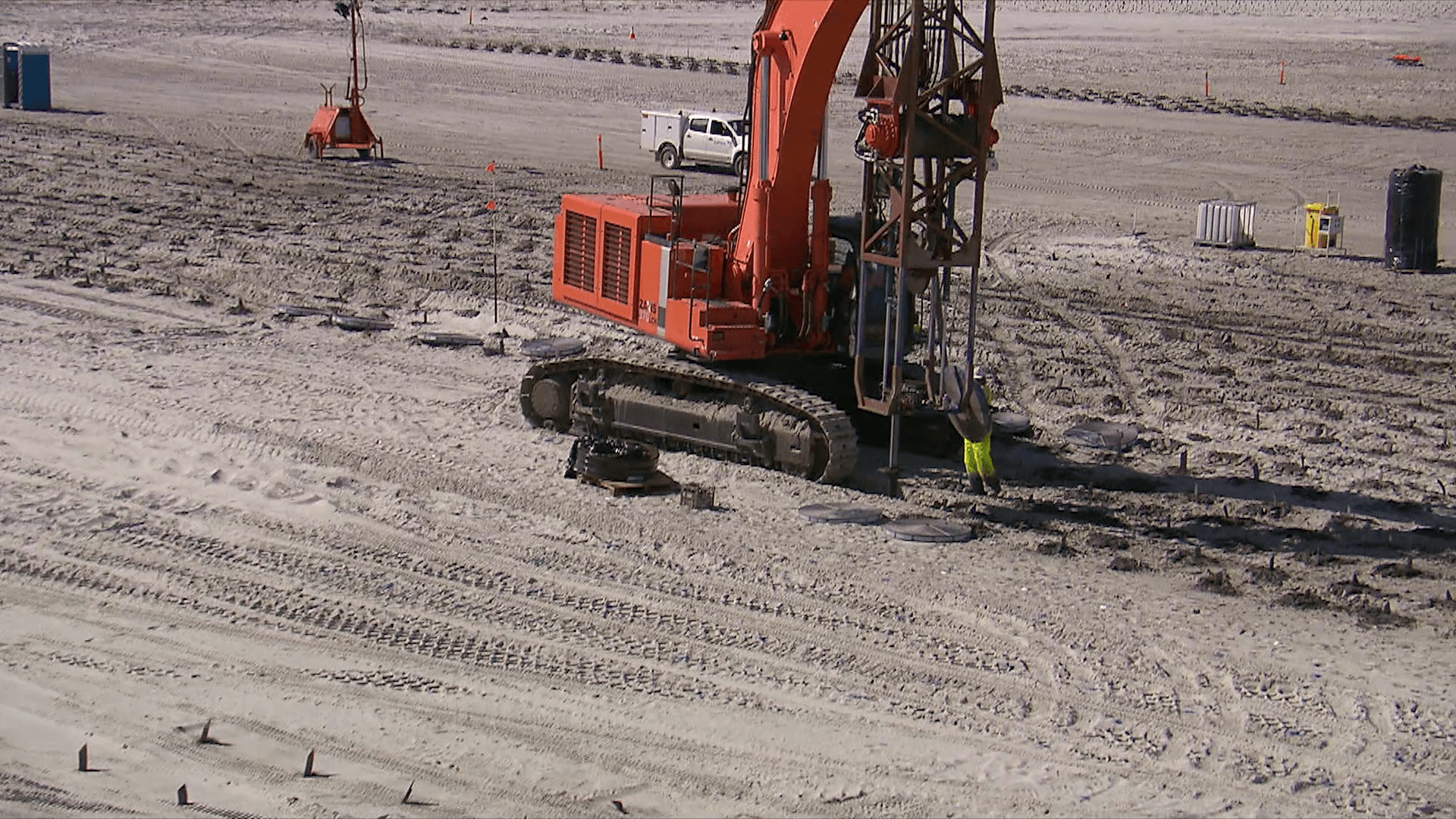

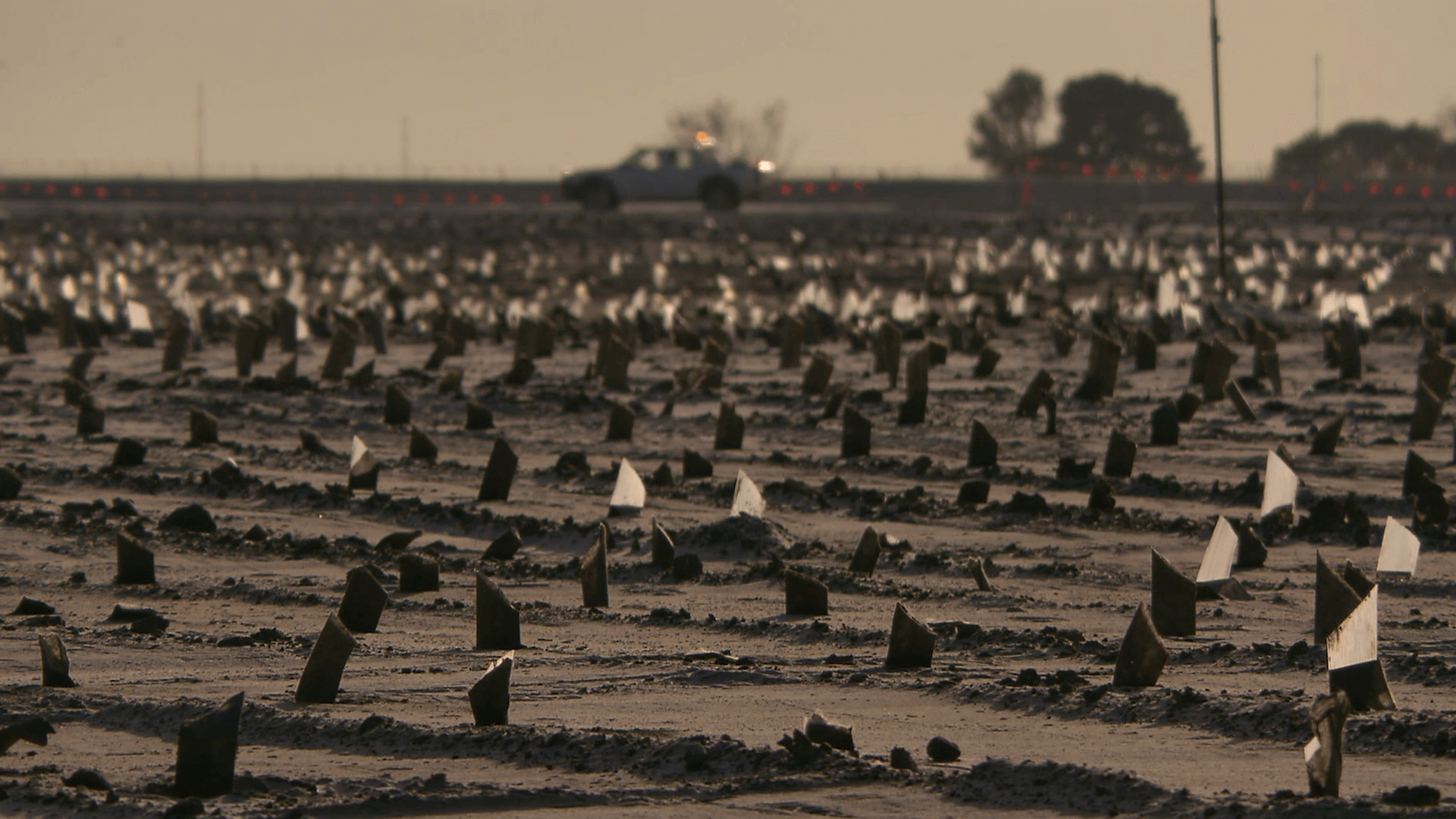

The team found a solution to the soil issues by incorporating 330,000 vertical wick drains, each extending 35 m below ground level - the largest wick drain installation project ever undertaken in Australia. This would draw water up to the surface from below ground to expedite the drying process.

“This reduced the settlement period from 5 years down to 3, but there was no guarantee it was going to work,” says Coughlan.

Using monitoring plates to track settlement, the project team could recalibrate the modelling and determine when the soil would be suitable for the airfield works to proceed.

After 3 years of settlement monitoring, and 5 years after commencing site preparation, the ground was suitable for airfield works to proceed.

Skyway, a joint venture between CPB Contractors and BMD, undertook the main airfield works which included a flexible pavement for the runway and rigid pavement for taxiways.

Due to the weakness of the soils, the runway pavement was designed with a deep subgrade comprising 2.5 m of compacted sand and a 600 mm layer of fine crushed rock, followed by a 60 mm asphalt pavement, totalling almost 3.2 m in depth from the base of the subgrade to the surface.

The taxiway consists of 1.5 m compacted sand, 200 mm modified fine crushed rock and a 500 mm thick concrete slab, totalling a depth of 2.2 m.

Meanwhile, a four-lane underpass, the Dryandra underpass, was delivered by McConnell Dowell. This included the installation of around 700 precast piles, driven to an average depth of 30 m, which are designed to support the weight of a fully-laden Airbus A380 (574 tonnes), and is future-proofed for even heavier aircraft up to 710 tonnes.

Another major hurdle experienced by the project team was the availability of potable water, with estimates suggesting that the project would exceed its allowable water usage limit. So, the team worked with the Luggage Point Wastewater Treatment Plant operator to arrange the supply of recycled water as an alternative to using potable water.

A $4.5 m pipeline was constructed, as additional works, to allow the use of recycled water for the project, helping to save potable water and, as an added bonus, reduce water usage costs by three quarters. The pipeline will now be available for continued use for airport operations.

The ambitious runway project, not only overcame appearingly insurmountable challenges, but was delivered ahead of schedule and $200 million under its $1.3 billion budget, not to mention the impact of a global pandemic.

Coughlan describes the project as a ‘resounding success’ with passion in his voice and a sense of great admiration for the project team and what’s been achieved. After 16 years as his baby, it’s easy to tell this was Coughlan’s life’s work.

“We wanted to establish an effective working relationship between my team as the client, the contractors, the consultants and the stakeholders. The Belgian dredging crew still say it’s one of the best projects they’ve ever worked on, and that’s attributable to the team dynamics.”

Coughlan attributes the success of the project to the unusually high collaboration and respectful approach that considers project participants, stakeholders, the general public and the environment alike, something that is rare on major infrastructure projects.

“This required buy-in from all the contractors from the beginning. We got everyone on the same page and offered incentives for performing to this high cultural standard.”

According to Coughlan, this stemmed from the very top within BAC. “Senior management approached me and said ‘Paul, we want to have as little impact on the environment as possible, how can we do that?’”

But it’s clear to see that this collaborative and respectful approach is intrinsic to Coughlans leadership style and his uncompromising focus on the big picture - delivering a runway that would benefit the community, not harm it.

This culture was epitomised in a dozer driver's actions one day, Coughlan recalls. As he began to push over a tree, he stopped when he saw a bird's nest, got out of the cab and pulled the nest out of the tree to relocate it.

“We had to establish what success looked like to us from the start. It was about eliminating safety risks, opening the lines of communication and instilling a project culture of care, consultation and full transparency to stakeholders.”

The team engaged conservation groups including Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland and Seagrass-Watch to undertake marine, fauna, seagrass and mangrove monitoring to ensure the dredging plumes did not have any adverse effect. Modelling was undertaken prior to dredging and then extensive monitoring, including aerial surveillance, was undertaken during dredging.

Working closely with the indigenous elders of the Brisbane Airport site and Moreton Bay Island was another unique aspect of the build. According to Coughlan, this entailed:

“Listening to them rather than telling them what we were going to do, understanding their indigenous history both on the land and in the bay and keeping them involved as construction evolved.”

Brisbane Airport is now the most efficient airport in Australia, with capacity to support the take-off and landing of up to 360,000 planes per year, thanks to its two parallel runways and central terminal building.

Australia has experienced a plethora of botched infrastructure projects in the last few years. But we can learn from Coughlan’s project management and leadership style to improve the rate of success for mega projects in our cities.

Eliminating the ‘us-vs-them’ mentality, and instead employing a strategy that promotes consultation, communication and teamwork reinforces that project success means something different to each stakeholder.

It’s important not to forget that infrastructure projects are, afterall, intended for the benefit of the community - so they shouldn’t have negative implications on that same community.

Of course, it has to start with the client which, on many occasions, is government.

“It feels very satisfying having completed this project successfully without incident or any disruption to the active runways, but at the same time, it is quite sad it’s over.”